I can remember campaigning with other disabled people to encourage the then Labour government to bring in anti-discrimination legislation that would not only protect us from discrimination but would also provide a big step towards obtaining our full Civil Rights. In effect we wanted it made unlawful to discriminate against us in respect of our impairments in relation to employment, the provision of goods and services, education, transport and accommodation. Something that most non-disabled people took for granted.

As the late Mike Oliver, a leading academic and disability rights campaigner said of the protests: “We had no resources, but we created a movement, which mobilised at its height hundreds of thousands of people.”

We also demanded that the government adopt the social model understanding of disability when constructing the Act, recognising that it was the barriers in society that disabled us and not our impairments.

Prior to the DDA, the first attempt to deal with the issue of disability was the Disabled Persons (Employment) Act 1944. This made it a legal requirement for companies with over 250 employees to employ a quota of disabled persons. This was now a toothless piece of legislation as there was not now anyone appointed to monitor those rights.

When the DDA was finally passed, we all felt that we had achieved something momentous. Most importantly, The DDA also now required schools and other providers to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ for disabled children. The duties were ‘anticipatory’, that is schools and other providers needed to think ahead and consider what they may need to do for disabled children before any problems arose. This was something completely new.

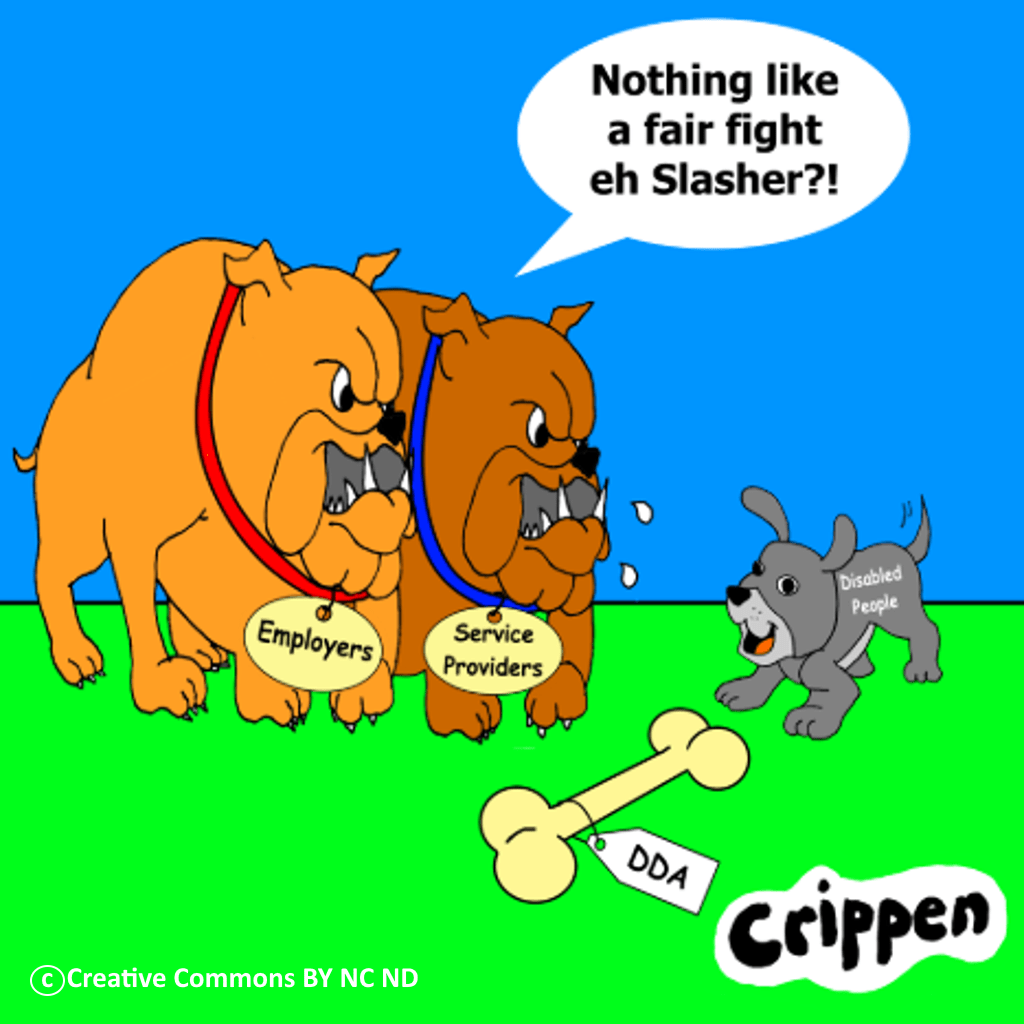

One of the core concepts of the DDA was the reasonable adjustments duty. Under this part of the Act it was incumbent for service providers to “avoid as far as possible by reasonable means the disadvantage which a disabled person experiences, because of their disability.” It made the DDA very different from older legislation in that the public sector had to think more carefully about making positive steps to end discrimination. However, the disabled people’s movement criticised the concept of businesses having to make reasonable adjustment because there were no clear guidelines regarding what was and what wasn’t ‘reasonable’. Activists called this part of the Act piecemeal’, ‘toothless’ and ‘tokenistic’.

So, apart from the un-reasonable adjustment clause, we now had our rights enshrined in law and nothing could take that away. How naive we were!

Things seemed to get better as in 1999 we also got our very own Disability Rights Commission (DRC); at the time, the DRC was the UK’s third equality commission alongside the Commission for Racial Equality and the Equal Opportunities Commission.

I also remember the final act of the DDA that came in, in the early 2000s declaring that all public transport had to be accessible by 2025. This seems to have been conveniently forgotten.

However, in 2006 the recently elected Tory government dropped its bombshell and introduced the Equality Act which brought together over 116 separate pieces of legislation into one single Act. They claimed that it “provided Britain with a discrimination law which protects individuals from unfair treatment and promotes a fair and more equal society”. The nine main pieces of legislation that merged included the Equal Pay Act 1970, the Sex Discrimination Act 1975, the Race Relations Act 1976 and of course the Disability Discrimination Act 1995.

What they hadn’t told us was that in replacing the DDA with the Equality Act, we lost all of the case law that had been accumulated through the courts. These were important cases which bolstered our rights to full and unrestricted access to society. These had now effectively been thrown away with the DDA and the other equality legislation.

Another nail in the coffin was the creation of the Equality and Human Rights Commission (EHRC) which merged the Commission for Racial Equality, the Equal Opportunities Commission and our own Disability Rights Commission.

The real rot started when the new coalition government introduced the upgraded Equality Act in 2010. They also started to downgrade protection on equality in general and specifically in areas of employment and public policy where disabled people had begun to make progress.

A fact sheet published by UNISON at the time sums up what happened next:

“The coalition government began to introduce austerity-wide measures in the UK – cuts to public spending, cuts to public sector jobs, reduction in funding to Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) and in particular, funding for disabled peoples’ organisations (DPOs). Devastating cuts were implemented through a draconian regime of reform of welfare benefits, scrapping Disability Living Allowance, introducing Personal Independence Payments (PIPs) and decimating the Access to Work Scheme. Disabled people where now being demonised and degraded for being disabled.”

And so, it goes on. The Coalition government cut £14 million of funding for 285 frontline organisations when it removed the EHRC’s grants budget. They also repealed the powers enabling employment tribunals to make recommendations that an employer change their policies or practice following a finding of discrimination.

On 29 July 2013, fees for lodging claims to the employment tribunal were introduced, which for discrimination cases are set at the higher of two levels. This has resulted in a significant fall in all areas of equality cases and specifically a 46 per cent fall in disability cases. This combined with the Government’s closure of the EHRC’s Helpline and casework service has left many disabled people in a position where they have no recourse to law when discriminated against.

And so it goes on. Disabled people have been forced back to the time when we had no effective legislation to protect us and we are once again denied our rightful place in society.

Come the revolution …

Originally published in Disability Arts Online

Description of cartoon: Two large, vicious looking dogs are sitting next to a playful puppy. The big dogs are identified as employers and service providers and the puppy is identified as disabled people. A large bone is on the ground between them labelled DDA. One of the big dogs is saying: “Nothing like a fair fight eh Slasher?!”